T

he voice had been addressing me for a few minutes, giving me instruction, leading me at alarming speeds towards the visualization process that serves as an airlock between the present and memories of past lives. I was on my back on a vinyl slab. My eyes were closed, my toes were sticking straight up in pointed refusal to relax, and I was nearly chewing my upper lip off so I wouldn't shriek with laughter. The last thing I felt was hypnotized.

"Imagine," the voice said evenly, "that you are in a very peaceful place. A room."

I saw walls paneled in dark wood. Rotting leatherbound books slouched together on shelves to my right, and ahead of me a long second-story window, opaque with dirt, overlooked an unkempt square of what had once been lawn. It wasn't exactly what I'd expected.

"There's a door to this room. It will lead to a set of stairs."

The stairs were scuffed and narrow.

"With each step you take, you will go deeper into your unconscious mind. Ten... nine..."

I reached a landing and a hairpin turn.

"Two... one. You are now in another place. What do you see?"

"Nothing." My voice was faint, almost childlike. Speaking was an effort. "I'm not in the body." Then I saw a water-studded clump of crabgrass. "It's chilly," I whispered.

"Look down. What are you wearing on your feet?"

I caught a glimpse of a small bare leg from just above the ankle to midcalf. My heart accelerated. Seconds later I burst into tears, overwhelmed. "It's so sad!" I cried.

"What's sad?"

"I don't know!"

"All right. You are going to move to another place in this scene. I want you to go there now. Look around, and describe what you see."

I saw the house from across the lawn: three stories high, very dark wood, with a gabled attic. Its many-paned windows blotted up light like black sponges. Then the picture wiggled roughly away until only darkness remained.

Regressive hypnosis—examining "prior lives" by inducing a hypnotic trance—is a very slippery proposition, combining as it does a theory of evolution that most Westerners reject on religious or scientific grounds, and a mind-control technique whose practical applications weren't recognized by the AMA until 1958. No one can say precisely how either process—reincarnation or hypnosis—works. But hypnosis can at least be demonstrated and partially explained.

In technical terms, hypnosis is simply a way of slowing down your brain waves to achieve an altered state of consciousness. Brain wave frequencies are measurable (we all know what a flat line on an EEG means) and are divided into four general categories which represent the speeds our minds shift through during a normal 24 hours. Beta is the highest speed: it's full consciousness. Alpha is the nebulous state we're in just before we fall asleep or wake up. Theta is the early stage of sleep, and Delta is deep sleep, or a coma.

In Beta we use the left, Mr. Spock-like hemisphere of the brain, which controls logic, analysis, and deductive reasoning. In Alpha, the lightest stage of a hypnotic trance, we move into the right hemisphere, home of imagination, intuition, creativity, dreams, and memory. Our capacity for accepting ideas is greatly enhanced, though we don't necessarily become more vulnerable. H.B. Gibson, author of Hypnosis: Its Nature and Therapeutic Uses, points out that "the hypnotized subject is not an automaton; he still retains his unique personal identity, and may refuse to accept suggestions which are not in keeping with his particular and habitual preferences."

Nearly everyone can be hypnotized (if he or she wants to be). But the degree to which someone is susceptible to hypnosis is an enduring facet of personality. Being suggestible—rushing off to eat nachos after an ecstatic discussion of Mexican food—is no indication of the ease with which you can be hypnotized. Thus far it appears that people with a child-like capability to immerse themselves in imaginary activities (daydreaming, fiction) during waking hours respond most dramatically.

Drama, though, usually isn't a big factor in the experience. Hypnosis is not the lurid event of legend: it doesn't require tracking the arcs of some pop-eyed psychiatrist's pocket watch, or imitating a chicken for appreciative strangers. If you've ever found yourself inexplicably paralyzed in front of a TV screen, you've been in a light trance. In fact, the difference between Beta and Alpha is so subtle that the common initial response to a session with a hypnotist is feeling like you've just bought the emperor's new clothes.

That's how Fred Rantz, current president of the Washington Society of Clinical Hypnotherapists, reacted when he was first put under. It was 1967; he was a five-state factory rep for Rockwell power tools, cruising his territory in an air-conditioned Buick and wolfing down unlimited expense-account meals. When his 6'3" frame hit 263 pounds, he called a hypnotherapist.

"I paid him 50 bucks and left feeling like I got ripped off," says Rantz, who has an air of genial menace reminiscent of Jack Nicholson. "Then I fasted for 10 days, went back and said, that was pretty interesting! What the hell did you do?"

He left Rockwell to learn the techniques, practiced at a clinic for two years, taught gigantic hypnosis class as the University of Washington's experimental college for five, and plunged into a lifestyle that guarantees most of his clients a sympathetic ear. "I've done it all," he says, "and had it all done to me."

Today 60 percent of his clients want to control their weight or smoking; 20 percent have problems ranging from stage fright to sexual difficulty; and 20 percent request past-life regression either from curiosity or because they have a feeling it will explain a current quirk of personality.

Rantz happened upon the phenomenon of regression unawares. "A woman came in because she had a fear of water," he explains "Being naive, I put her under and told her to go back to the place where the fear started. In about 30 seconds she began to gasp and choke, so I took her back further. Turned out she'd been a sailor who'd been shipwrecked. I just sat there with my mouth open, asking, and then what happened? She remembered it all when she came out of it—people seem to get what they're ready for."

Fifteen hundred regressions later, Rantz says, "It kind of humbles me. I direct it, in a way, but the other person does all the work."

He practices in his Kirkland home in a semi-collegiate atmosphere of crammed bookshelves and stale incense. I had to fill out a release form that included questions on any surgery or counseling I'd undergone. Then Rantz carefully explained the whole show to me, drawing a diagram upside-down for my benefit, promising with a wink not to hurry me through anything interesting like a wedding night. I paid him $150.

"After doing this for 13 years," he told me, "I'm not willing to do five hours for $25. And money is a motivator. If you get somethin' for nothin' what's it worth to you?"

Finally I reclined on his spare, sinister black couch. He started talking. I had a terrible time keeping up with his suggestions: I'd still be concentrating on my knees when he'd tell me to relax my scalp.

"You will hear all the sounds of the universe," he crooned, his inflections rising, falling, rising. Voices... bells... dogs... wind...rain..."

In the silence that followed, my stomach growled. Then, in juicy, explosive reply, his growled. I sank my teeth into my upper lip and thought, he's right—money is a motivator.

F

our and a half hours later—it felt like one—I'd been through a sketchy examination of six lives. Rantz used what I would come to recognize as a standard procedure for hypnotic regression. After an introductory, one-time-only relaxation process, I'd be told to imagine myself in a tranquil setting. Then I'd mentally descend a stairway or use another vehicle to propel myself into another life. Once there, I'd look down to see what I was standing on, and what I was wearing on my feet. I'd hit the high points of that life, go through the death experience, and then check with my Masters and Guides to learn the purpose of it all.

Masters and Guides are well-meaning if amorphous entities. They can be thought of as spirits dwelling on the astral plane, or as manifestations of your Higher Self (a.k.a. your intuition, or your soul). Some people experience them as balls of light; some see Jesus; some meet eccentrically dressed creatures in human form. I didn't see anybody (or thing), but tidy moral summaries came to me anyway—"The purpose of that life was to learn compassion," or, "He should have tried to teach the tribe his skill at hunting."

The following are much-reduced descriptions of the six lives. I actually recorded nine wide-margin, single-spaced, typed, pages of details after the session.

First life. The dark wooden house; great sadness.

Second life. A Mexican peasant named Jacinta. She had a small brother and a fat bronzed mother with eyebrows like black birdwings. At 16 Jacinta was violently courted by the leader of a pack of Mexican cowboys. "I knew him before (in another life)", she said. "He never learns that you can't force someone to love you." She married someone else, had children, and watched in cheerful resignation as her teeth fell out. Jacinta breather her last as a desiccated grandmother, lying under a blanket close to a dirt floor. The soul left the body through the head and went to meet a spirit presence waiting in a forest of saguaro.

Third life. A splay-footed Stone Age male, who grew up in a tribe of about a dozen before fire or language were known. He was fairly alert, but found no rudimentary glints of intelligence among his peers, and broke away to live on his own in deep woods. A profound if visceral sense of unity with his surroundings eased his loneliness. He died at about 40 under a tree. The soul hovered a few hundred feet overhead until the bones of his hands looked like stars in the soil.

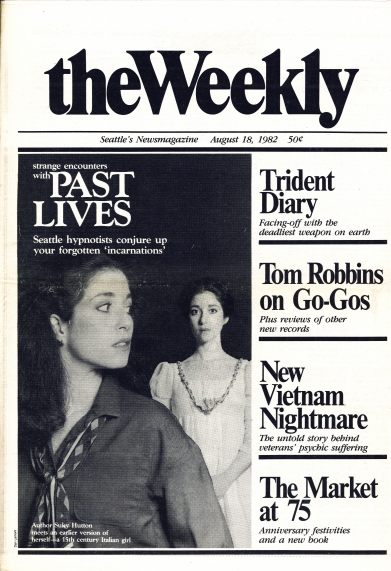

Fourth life. A 15-year-old girl in 15th-centuary Italy, daughter of a robust, intellectual merchant. She felt she had three options in life: to be married, to become a nun, or to run away. She bribed sailors bringing imports to her father to sneak her aboard their ship, cut off her hair, and sailed south until the the ship reached a coastline with a brush-cut of palms. She went ashore in a rowboat, contracted a fever, and died in a hut with a raging headache, worried black faces above her.

Fifth life. A prosperous Arab horsebreeder with honed easthetic sensibilities and little talent for listening. He had a house with a labyrinth-like garden leading to the sea, a decorous wife, three sons, and a relationship of mutual appetite and respect with a shrewd, expertly-perfumed courtesan. His middle son, whom he'd encouraged in the arts of war, died in battle; the loss intensified a courteous estrangement with his wife. His mistress vanished without notice, taking her serving-woman with her. Not long after he died while sitting in his garden. "People are sad," he observed, "but nobody's heart will break."

Sixth life. "A fierce-looking woman with deepset eyes, powerful hands, and extensive medicinal knowledge of herbs. She lived in a cave dug from a hillside above Granada in 16th-century Spain. Raised by gypsies, but not one herself, she left them to pursue a solitary vocation of healing. She died of old age, tended by nuns in a mountainside convent.

First life, second look. Jane, a neglected 11-year-old living in the northeastern U.S. in 1817. Her parents were crazy. Before she'd been born they'd created an arbitrary, hermetically sealed universe of their own, shutting out logic and other people. They tolerated but only rarely acknowledged her.

There were no rules in that house. Jane never knew when her parents might eat or sleep, and because her parents were unconcerned with the physical world, the rooms were filthy, furred with cobwebs. She fended for herself, hurt and bewildered.

A woman from town brought second-hand clothes and her brother, a preacher, to the house, but Jane's parents sat side by side on the horsehair sofa and slowly drove them out. A few years later Jane escaped to live with this woman and became a devout, even dogmatic Christian. "There is order in God's ways," she explained primly. "This is as close to heaven as I'll come in this life."

Not so—she came closer as a missionary in Indonesia, teaching small children. She met her husband there: Harry, a "bumpkin" and very kind man, somehow attached to a local British military outpost. They had two children and eventually moved to the east coast of England. Jane was taking an afternoon walk when she slipped off a dock and drowned.

None of these lives were what I'd both feared and hoped for: they lacked the clarity of movies, let alone the 3-D immediacy of dreams. The best way to simulate the experience is to go through the following exercise. Keep your eyes open. Think of a friend's face and look at it, feature by feature. You're seeing with your mind's eye. This muted form of perception is usually what transpires in a trance.

Murky as my impressions had been, I'd received lots of them. Where had they come from? The Marianas Trenches of my 1982 psyche? The irresistible urge hypnotized subjects feel to respond to all questions? A penchant for storytelling combined with 20 years' worth of historical reading? ("If this is the Arab world, that must be the call of the muezzin!") Only a few pieces of information seemed brand new. I looked up a map of Indonesia and promptly felt drawn to the geographical area of British North Borneo. But during the time Jane would have lived there, British North Borneo was under Dutch rule, making the existence of Harry's military outpost unlikely. I did confirm for myself that Granada lies at the foot of a mountain range. All in all, pretty wispy factual substantiation for six lives.

One thing haunted me: Jane's life. It has flown out unbidden, the way intense associations do when I hear a piece of music or find myself on a street I've avoided for years. In those cases I don't ask for pictures or feelings: I'm assaulted by them. I knew the floorplan of her house, and I knew her parents: the brutally indifferent, remotely amused mother with the pinned-up ash-blonde hair; the intense and yet aimless father. They did not correspond to my parents or anyone else I know.

A

nother round with a different regressionist seemed in order. I called another number in a classified ad and discovered a woman with a mission: Joy Tunnell.

Unlike Rantz, an unabashed salesman, Tunnell radiates charismatic mysticism. She's convinced that people seek out regressions when their higher selves have urgent messages to communicate. Her fee—$25 for 90 minutes—is in keeping with her service ethic; better yet, she makes house calls.

"How will I know you?" I asked, before meeting her for lunch.

"You can't miss me," she said. "I'm 5'9", weigh 250 pounds, and will be wearing a magenta dress. I'm very striking."

Whatever I'm expecting, it wasn't a former debutante and president of Jaycee Wives in discreet makeup and raw silk. But then whatever Tunnell had expected from life, it wasn't fulfilling destiny by becoming part of a New Age holistic healing team. During the sixties she lived in a Dallas suburb, wore mink, sent her children to private schools, and wondered what was missing. She had always eschewed religion, but at a friend's suggestion attended a service at the Today Church. It was a storefront operation where a woman in hot pink hostess pajamas played compositions of her own on a piano. Tunnell swallowed her way through a few moments of culture shock and wept. "I was home," she says.

For the next 10 years she took every metaphysical course the church offered. Revelations accosted her from all sides: she was a channel for eminent yogi Paramahansa Yogananda, she was five million years old, she was on Earth to assist humankind through an upcoming fall-of-Atlantis scenario. "Oh, sure," she said.

But she kept listening. Her Masters and Guides told her that she was to develop past-life regression as a tool to help people hook up with their higher selves and eternality. In 1980, after doing 200 regressions in six weeks, she flew to Phoenix to take a regressive hypnosis course from Dick Sutphen, who is probably the nation's foremost expert on the subject. Then she had a dream instructing her to attend a school of naturopathic medicine. One of the best is in Seattle (a city known as a U.S. psychic hot spot). Tunnell, a divorcee with married children, was free to pull up stakes and move to the Northwest. A few weeks after arriving she knew that her brand of healing wasn't naturopathic medicine. She started a new life as a fulltime regressionist and teacher of advanced soul evolution.

Tunnell felt I should watch someone else being regressed, so I invited a friend I'll call Amy who had taken notes for me during the session with Rantz. Amy, like many people, didn't think she had any past lives. She settled onto my couch resignedly, and I tucked an afghan around her, since body temperature tends to drop during hypnosis. Tunnell, in classic pumps and pearls, murmured us all into Alpha.

Not long before, I'd seen part of an old movie on the order of Ripley's Believe It Or Not that examined some less-trodden byways of human behavior, including past-life regressions. It featured a normal housewife reliving a prior-life drowning at age 6. Her head thrashed from side to side; she screamed in terror—it was gripping and highly suspect footage.

Amy (another normal housewife) later reported feeling as though she was falling down a chute in utter blackness. Then Tunnell started asking her questions. At first Amy's voice was low and breathless; then her head tossed violently from side to side and she cried out "Why am I so alone?" with such pure, helpless, high-voltage anguish that tears sprang to my eyes.

It turned out that she was a seven-year-old orphan named Frances living with a malevolent aunt. Frances grew up to marry a storekeeper in Montana. Her life was hectic, and when one of her sons died accidentally she blamed herself for negligence. Tunnell periodically asks if people encountered in past lives are anyone the subject knows in the present; when she enquired, Amy gave her current husband's name to identify Frances's dead son.

"So now you owe him your life," said Tunnell, not knowing who the name indicated, or that she had just described Amy's role for years in a painfully erratic marriage. (Sutphen has written two books on the theory that many husbands and wives knew each other in some way in prior lives.)

Amy was a star subject. Her voice changed with each past life; she seemed to become Frances, as well as, eventually, a doughty adolescent Viking warrior and an effervescent Irishwoman.

I merely returned to 15th-century Italy in a kind of regressive re-run to learn that my name had been Eila (not your average Italian tag), and identified Eila's father as someone who recently told me, after years of knowing me, that he'd figured out I was his daughter. I was also a Northwest Indian woman during the early 1700s and a dogged rice-tiller named Lao.

There were times when Tunnell's regression technique felt too direct. For example, instead of asking "What's taking place now?", she might say "And you don't have form, do you?" Leading questions are a trap. A recent article in Vogue, describing the memory studies of Dr. Elizabeth Loftus at the University of Washington, points out that "if you ask 'How fast was the car going when it passed the barn on the country road?' people will remember the speed and also the barn—though no barn existed."

Tunnell's enquiries might be in part attributable to her psychic powers. Experienced regressionists all seem to agree that telepathy increases during hypnotism. Subjects report receiving the hypnotist's instructions before they've been spoken aloud. Tunnell, who focuses intently on her subjects intently throughout every second of a regression, says she picks up impressions of their experiences.

Past-life manipulations aside, Tunnell's self-descibed purpose on Earth is using regressions to connect people with divinity. Amy, who later felt she'd invented her three lives, has no quarrel with Tunnell's effectiveness in that respect. "She certainly took me to a very beautiful place I'd never been to before," she says.

Amy experienced her Masters and Guides—or one of them—as a deeply comforting presence of blue-white light. I was, at last, introduced to a couple of mine: Nicholas, an athletic-looking blond Greek, and Luana, a small, diaphanously-dressed female with long black hair. They communicated with me mind-to-mind; their faces were quite expressive.

The encounter was pleasant. But one of the most extraordinary experiences I've ever had occurred after Lao died. I was disconcerted; I didn't know where I was supposed to go next. Then, "Oh—I'm going home," I announced, relieved and ecstatic. I felt I was traveling a vast distance at unthinkable speed. Suddenly I arrived at a space I'd always believed in, but never known: a signing, rapturous communion of consciousness, an infinite sea of like minds or spirits. I was separately conscious, yet fully aware of and connected to all consciousness. There were no forms—nothing existed but love, intelligence, and joy. I wasn't interested in trying to speak for the tape recorder, or in leaving.

"The soul's longing to be where you are is what moves us on," said Tunnell gently, before bringing me back.

E

xhilarating? Yes. Possible to research? No, except for a date Amy gave for a plague in Ireland—which turned out to be incorrect. When it came to my lives, I couldn't find details that I wouldn't have been able to conjure up while wide awake.

But hypnosis is like anything else—the more often you do it, the more proficient you become. I was now a more conditioned subject, and I'd located a hypnotherapist who is contributing to the work of Dr. Helen Wambach.

Wambach, a psychiatrist and author, became involved with past-life regression when she visited a Quaker memorial and spontaneously clicked into another life. First upset, then fascinated, she developed formal research methods to document the patterns of past-life regression. Today she's involved in the statistical, computerized analysis of data gathered in consistent formats from thousands of regressions (data which is showing surprising correlations to recorded history).

Dora Wilson, an oft-certified hypnotherapist practicing in a conventional office in Auburn, has a common-sense view of life that doubtless served her well during her five years as a nurse in a Texas mental institution and now makes her a reliable contributor to Wambach's work. She shies away from anything smacking of the Twilight Zone.

"I don't like the word reincarnation," she declares. "It brings up other philosophies, like transmigration." (Transmigration is the passing of the soul from one physical body to another. It often implies a drastic switch, e.g. coming back as a tarantula. After reading nearly two dozen books on reincarnation and interviewing four regressionists, I have yet to stumble on a case history involving anything but humans recycling as humans.

What Wilson does feel comfortable with is the therapeutic value of past-life regression, which is why she advertised it in the Yellow Pages this year. "I debated, but then I said, hey, wait a minute, this is an effective tool. Somebody's got to break the ice."

She discovered its healing properties while working with a six-year-old girl who had a lifelong history of stomach ailments. Not even exploratory had pinpointed a cause. "After our second session I kind of stopped in midair—I go a lot with my intuition—and asked, Is this problem in some way connected with a past life? Nobody was more surprised than me when the answer was yes."

The little girl had been a little boy in the 18th century. He was running through a field carrying a sharp stick when he fell and pierced his stomach. "The pain carried into the next life," Wilson said. "That was ten years ago. It alerted me to other carryovers from past lives. I find regression very beneficial for certain individuals."

Because I was familiar with Wambach's work, and had explained my desire for traceable information, Wilson used one of the doctor's most meticulous inductions on me, literally reading from a script. It began with a geography roster and included suggestions to observe everything from clothing from clothing to religious ceremony. Wilson did not have me respond verbally while I was under. "People seem to ge so much more when they don't have to keep changing from the right hemisphere of the brain to the speech centers in the left," she explains.

It might have been the fan humming on Wilson's office floor, or Wambach's complicated induction, or not having to talk, but I almost fell asleep. Then, abruptly, I experienced something I'd been waiting for: the clear, comprehensive sensations of waking life. I was standing in mottled sunlight on dusty hard ground. A small boy with a breathtakingly sweet face was smiling up at me. I bent to touch my forehead to his; I felt the bump of his silky black hair against my face and knew he was the center of my life.

Unfortunately, the effect thinned out fast. I was back to peering through the glass, darkly, feeling as though I was dredging up appropriate details: my gauzy but rough orange sari; a riverside cremation. I identified myself as Nahid (which sounds Persian to me), a young woman living in southwest India. Nahid died of uterine cancer in her 20s.

Wilson, a motherly, voluble woman in her 50s who kept calling me "babe", had me fill out a questionnaire afterwards and saw me out as though we'd just met at a family picnic. Her sessions run $45 an hour, $90 for 90 minutes, and $50 for participation in a group regression.

I drove off bemused. Each time I went under, something new happened. But I still didn't have so much as a last name or the name of a specific town.

The next morning, before I was fully awake, I was standing over the sink when I automatically began to part my hair in the center and draw it back into a bun. It was Nahid's hairstyle, not mine.

During this time two more of my friends were regressed. I was present when one, a professional actor, went under. Despite his training, he never stepped out of his offstage persona. He made Amy look like she'd been auditioning for Lee Strasberg.

Another friend, an ex-journalist, is certain she created two lives as an oblique guide to self-analysis. She compares regression to the dolls that police ask molested children to respond to: like the dolls, regression puts trauma at one remove.

Several weeks after my regression, my ex-journalist friend showed me selected pictures from a vacation. "No, no, I gotta see them all," I said, and thumbed through the stack. Near the end I caught my breath: I was looking at a near-twin of Jane's dark wooden house.

"There are houses like that all over New England," said my friend, who identified it as the House of Seven Gables. I've never been to the northeastern U.S., except New York, nor have I ever read the book. To the best of my knowledge I'd never seen a house like that until I was hypnotized. But then, if someone showed me a dialogue I'd memorized for an eighth-grade Spanish class, I probably wouldn't remember that either.

T

his was it—my last factfinding mission with a hypnotist. I went under to a voice and a metronome set to slow my heartbeat. Instead of cooling off, I felt deliciously warm and insubstantial, with a glow in each palm. After a while the voice suggested that I was moving through a long tunnel of trees toward a pinpoint of light, to the count of five.

"Four... five."

I began smiling.

"Look down... what are you wearing on your feet?"

My smile grew wider. Finally, "Not important," I mumbled, and lapsed into silence.

Something I have never been able to do, and something hypnotic regressionists always seem to be suggesting, is to visualize white light. You're supposed to bathe things in it to clear up mysteries; surround your limbs, not to mention entrails, in it to cleanse them, and summon an enveloping fog of it for spiritual protection. I could never imagine it so much as enveloping my pinkie.

But when I reached the end of the forest tunnel, white light was all I saw; it was all there was. I felt as though my eyes, which were shut, were completely open; actually I seemed to have been distilled into vision, because I didn't have a body. It was comparable to having my eyes open in complete, impenetrable darkness, but instead of feeling disoriented, I felt ridiculously pleased.

During the rest of the session I skipped back to visit two lives—that of the Stone Age male, and, for a few very apprehension-filled moments, of Jane. Luana appeared and I received the distinct impression, even as our faces were inches away from one another, that we were the same being.

I woke up feeling grand. Larry Iverson, the hypnotist, was grinning. "Tell me about the white light," he said.

Iverson is a 32-year-old ex-elder of the Mormon Church; he's articulate, modest, and slightly interview-shy because of publicity he's received for his psychic gifts. He was 30 credits away from a a pre-med degree in chemistry, with a 3.8 grade average, when his higher self informed him he wasn't going to medical school. He turned to studying comparative philosophy and religion and emerged a Tzaddi minister, Tzaddi being a faith that "emphasizes looking at the whole to better understand a part". In 1979 he changed his focus from teaching via the Tzaddi church to hypnotherapy. He and Wilson are the only two hypnotists in the Seattle region who advertise regression (the third number is disconnected); his hourly rate is $30.

"I seem to attract people with really heavy emotional problems," he says. "Sometimes they can be helped through a situation called a past life. If they get a mental movie that helps them understand their problems, great.

"I can't say I automatically believe in reincarnation. I've looked through too many microscopes and dissected things; I like a scientific approach. There are a lot of ways to perceive what happens during a regression. Einstein theorized that energy can't be created or destroyed; it changes, but it doesn't disappear. Reincarnation could simply be people picking up on the energy from earlier times.

"Regressive hypnosis is just a tool—it gives people choices when it comes to understanding and being responsible for themselves. It's a way to increase consciousness, but it's only one of many."

Iverson's maybe-yes, maybe-no perspective on what regressive hypnosis represents is shared by Rantz, Tunnell, and Wilson. All three of them have been regressed, all report that the experience was "very interesting", and none thinks it would be reasonable to state that what they experienced were definitely past lives. They agree that the point of hypnotic regression is personal enlightenment, not historical research, a sentiment echoed throughout the literature on the subject. Even Wambach, queen of the hard-nosed data collectors, writes that "for many subjects, it is the emotional level of the experience that has meaning rather than the intellectual content."

Tunnell, whose life has been radically altered by past-life regression, does not invest it with more than therapeutic and spiritual values. What if, she was asked, Amy returned to Frances's life five years from now and identified her dead son as someone else. Tunnell thought it over and replied that it would be just as valid, because it's the message in a situation that counts.

The more I was regressed, the less I thought of hypnotism as an entree to past lives. Bizarre and enjoyable as it would be to regard myself as the latest version of an essence that was once a hedonistic Arab and a Spanish healer, it seems more plausible to view the experience as a series of dreams nudged along by hypnotist intermediaries.

I wouldn't argue that what wrings emotion out of regressed subjects is self-recognition. But just as dreams often reveal truths in symbolic terms, sometimes with a ruthlessness that waking consciousness would flinch from, the lives unearthed in regressions seem to be expansions of dominant fears, faults, strengths, or hopes. This is where the chicken or egg quandary looms large: are you having trouble with something today because you wrangled unsuccessfully with it two centuries ago? Or is the right hemisphere of your brain supplying a marvelously constructed explanation, much like a dream, to give you fresh perspective on your current life?

N

o theory on the process is altogether satisfying. More than three months after I first encountered Jane, she retains a strangely fullblown, autonomous insistence I've never associated with dreams. But that's the allure of hypnotic regression. It defies irrefutable definition; it's an adventure.

In fact it might be a main line to the ultimate adventure: death. Carl Jung, in an essay titled "The Soul and Death", describes life as "no more than the initial disturbance of a perpetual state of rest which forever attempts to re-establish itself". If this is true, then it's not surprising that death is the one thing described with remarkable consistency during regressions, or that the reports of those who "die" during a regression and those who have experienced clinical death match up.

Here are some sample observations.

Amy (in a trance): "It's a feeling of peace and joy, as I knew." The actor (also in a trance): "Um-hm... it's a lot easier being dead." The ex-journalist: "A tremendous relief, as though a weight had been lifted."

Regressed subject, Reincarnation, Key to Immortality, Moore and Douglas: "...Not an ending, a beginning, but a returning to a joyous time... a great union with things known before, understood before."

Regressed subject, Reliving Past Lives, Wambach: "Death was the best part of the trip."

Dora Wilson was pronounced dead at 18 during childbirth: "They said, we lost her. I was excited; I was going into white light that became brighter and brighter. I had a sense of freedom, of ecstasy, of expectancy. I didn't see anyone—not Jesus, God, or Aunt Jane. I was going home." She returned when a voice told her she would live to raise her daughter.

Before my last regression began, Iverson asked me what I wanted out of the session. "Confirmation," I said. "Specific facts." But I was already starting to realize that the Dragnet approach and regression don't mix. So I told him about Lao's death, and going "home".

"I'd like to go there again," I said, "though I get the feeling it's not something I can control."

"It won't ever be exactly the same," Iverson said. "But you can go back, and you'll recognize it."

Minutes later, I was euphorically, weightlessly centered in white light. When I awoke Iverson had me describe it to him. Then he told me that fewer than one in 100 people he's regressed have had that experience.

Maybe I was being thumped across the brow with a white-light truncheon. All along, I'd been tracking the long-shot promise of documentation, unsatisfied with my vague visions of cedar totems and Mexican cowboy hats. I craved a newspaper headline; an inscribed page of family Bible; a spoken, tape-recorded phrase of unmistakably Renaissance Italian. I fretted that there was nothing to prove that I wasn't spinning one openwork karmic yarn after another to appease my hypnotists and myself.

In one sense, there wasn't. But the proof of what you learn via regression, at the risk of sounding like a weak Kung Fu script, is finally something felt, not analyzed. I don't expect to stroll down a Mediterranean street one day and spontaneously regress into Eila, or to learn that any of those people, from Lao to Nahid, ever lived outside my skull. That doesn't mean I don't acknowledge them as familiar. They are indisputably part of me, ancient or not, and I'm sure they will continue to keep me company in the erratic fashion of memories.

B

ut what I carried away from past-life regression was not what I came looking for.

Wilson, when she was first regressed, demanded "How do I know this is true?" The answer she was given was the one she gives others now: that the feelings which illuminate your experience tell you if it's the truth.

I feel that I was told something twice—shown the existence of something glorious, immutable, and yet fluid; something all religions have names for but which transcends words; something that is outside the restraints of time or space.

I expected to finish this article by coolly proposing what Jung would call "opinions of which the heart knows nothing"—along with, ideally, some sensationally obscure and provocative evidence of prior life dug from the unused 90 percent of my brain. I have to finish, instead, by saying that I don't think hypnotic regression provides a reliable straight shot to past lives, but that it offered me far more: an unsolicited glimpse of what my heart knew as eternal life.